As a child grows, their eyesight can change rapidly. Regular eye exams are crucial to ensure their vision is developing properly and that any issues are addressed promptly. Schools often offer vision screenings to students, but it's important to understand the difference between a vision screening and a comprehensive eye test. A vision screening is a quick and simple test that aims to identify children who may have vision problems. During a vision screening, the child is usually asked to read letters on a chart or identify shapes and colors on a card. This test is performed by school nurses or volunteers and typically lasts a few minutes per child. While a vision screening can identify children who may have obvious vision problems, it is not a comprehensive eye exam. A vision screening does not check for eye health issues or diagnose eye diseases that may be affecting the child's vision. It's important to remember that a child may pass a vision screening but still have an undiagnosed eye condition. A comprehensive eye exam, on the other hand, is a thorough evaluation of a child's eye health and vision. This type of exam is performed by an optometrist or ophthalmologist. During a comprehensive eye exam, the doctor will evaluate the child's eye health, check for eye diseases and conditions, and perform a vision test. In addition to checking for nearsightedness, farsightedness, and astigmatism, a comprehensive eye exam can detect more serious eye conditions, such as amblyopia (lazy eye), strabismus (crossed or turned eye), and color blindness. These conditions can often be successfully treated if caught early, but they may not be detected during a simple vision screening. While vision screenings are an important first step in identifying children who may have vision problems, a comprehensive eye exam is necessary to ensure that a child's eye health and vision are thoroughly evaluated. Fortunately we provide comprehensive eye exams at schools, which provide added convenience to families. Parents or guardians should make sure their children receive regular eye exams from a qualified eye care professional to ensure that any potential issues are addressed promptly.

1 Comment

Hopkins pediatric ophthalmologist Dr. Megan Collins has been conducting screenings and administering glasses to students in a dozen Baltimore elementary schools to produce a first-of-its-kind study that attempts to link vision deficiencies and literacy in a school-based population. Erica L Green investigates the implications of this study in a fascinating article in The Baltimore Sun. Click the link to learn more about her study. The evidence is clear that there is a continual rise in short-sightedness of epic proportions. This article was originally written by Dr Cathy Wittman on her blog, wittmanvision.com. You can view the original post here.

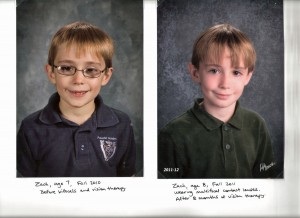

I started a Pinterest board about Vision Therapy last year, and it has gained followers quickly. If you have never used Pinterest, it is a way to save web pages from the internet similar to, but much more fun than, “bookmarks” or “favorites” in your web browser. Instead of saving the web pages as titles or links in a drop down, you save the webpages as “pins” using a photo. On Christmas Eve last year, I received an intriguing facebook message from a pediatrician. She told me the story about how her son completed a vision therapy program one year ago. One of the most compelling statements that she wrote was, “His dev opt saved his life and our family.” She went on to write that two years ago “life was hell”. Her son had been diagnosed with intermittent accommodative esotropia, amblyopia, ADD, and severe vestibular processing problems. He was seeing a pediatric psychiatrist, and the situation was dire. She was worried that he would have to be hospitalized for his behavioral issues. Their family has an amazing story. I asked her if I could interview her for a blog post. I created this blog with their story as my motivation. She and her husband, a radiologist, have seen how vision therapy can change lives. It is important to share stories like this one because vision therapy is effective. Dr. Wittman: Dr. Jennings, thank you so much for allowing me to interview you about your son, Zach. When did you first hear about vision therapy, and as a pediatrician (and wife of a radiologist), what were your initial thoughts? Dr. Jennings: In December of 2010, we had taken Zach to see a specialist for AD/HD in New York. On the flight home, a stranger sat in the aisle with Zach and me. He was very nice, and we chatted about our trip and the reason for going to New York. He had a website link that he thought might be useful to me, and asked for my email. A month later, he emailed me a link to a news story about convergence insufficiency and wondered if vision therapy might be helpful to Zach. I watched the news story and found many similarities between the child in the story with CI and Zach, however, Zach’s problem was convergence excess. I did not understand convergence problems or vision therapy or how it could help. I asked our ophthalmologist who had seen Zach since age 5 ½ for his opinion. He said that I should read the statement by the AAO and the AAP that came out in 2009. He did not think it would be helpful and thought it would be costly, so he recommended that I not take Zach to a developmental optometrist. Initially, I agreed, and I did not schedule Zach an appointment. I reread the statement. Then I picked up Zach from school and saw his frustration, and I thought about convergence insufficiency and convergence excess. I reasoned that they were really the same problem, just different degrees of eyes not converging in the same location. Why could vision therapy help convergence insufficiency but not convergence excess? Did those who said it did not work really know what they were talking about? I hoped that there was something out there that could help my son. I called the closest clinic and asked how much a developmental vision exam was? I decided that I would rather spend the money and later think I had wasted it than to not spend it and always wonder if I had missed an opportunity to help my son. At Zach’s developmental vision appointment, first I was told that he needed bifocals. I was surprised by this, as nobody had ever checked his near vision by having him read letters in the near range. I had never questioned this before because I trusted the ophthalmologist and felt that Zach was getting the best care he could get. He had had some testing done using cards that were held near, such as the binocular vision assessment using 3D glasses to look at an image of a fly and some other images of various animals with one of four projecting outward that he was supposed to identify. In the past, the thoughts were that he had been able to see the 3D images, though he never got every one of them correct. He had not had that type of testing done in at least 3 or 4 years. After his vision exam and refraction, he went to a room with a computer and 3D glasses and did a program by Home Therapy Solutions called BVA. I know they tested his accommodation, saccadic movements, and pursuits, but I don’t really remember much about that part. The first part they did was the phoria test which required Zach to look at a blue circle and a red plus while wearing the red/blue glasses. His left eye could see the circle, and his right eye saw the plus. The circle was fixed, and the plus could be moved with a remote control. He was instructed to move the plus so that it directly overlaid the circle, like crosshairs on a gun. The circle had little white marks on it where the plus would fit. When Zach saw the plus as on top of the circle, the plus was actually located several inches to the left of the circle because his eyes were crossed. Suddenly, as I realized what he saw and how different it was from what he was supposed to see, I began to understand my son. It was a very emotional appointment for me. I do not remember much else because as he was being tested, I kept remembering different things that had happened in the past and wondered if these things were related to his vision. For example, he had never shown any interest in any sport that involved a ball. He could not catch a ball if his life had depended upon it. A week earlier he had been trying to flip a coin and catch it in the air. He had a huge meltdown after he became frustrated because he could never catch it. At age 3 Zach had begun sounding out words and trying to read, but by kindergarten, he had no interest in reading. He was the kind of kid who wanted to know everything there was to know about a topic of interest, yet he had no interest in reading that information for himself at age 7. When his teacher tested his reading ability at the beginning of 2ndgrade, she found his level to be 6 months into 3rd grade. She thought he was lazy and unmotivated. Suddenly, I realized that when he looked at books, he was seeing double and everything was out of focus. Forcing himself to read was like making him lift 20 pound weights with his eyeballs. No wonder he was frustrated! I did not know anything about vision therapy, however, I did understand that nobody had ever done testing on my child that had revealed so much information to me before. I hoped it would help and was willing to do whatever it took on my part to support my child as he did therapy. At that point, I just trusted that the doctor who had actually identified significant problems might know something about how to fix them. My plan was to read everything I could so that I could understand therapy and understand why I needed to do what was asked of me as a parent. First I read Jillian’s Story, by Robin Benoit. I was amazed by the outcome Jillian had with vision therapy, and I saw many similarities in what Jillian had experienced and what my son was experiencing. This book gave me hope for my son. Next I read Fixing My Gaze, by Sue Barry, PhD, about how she acquired 3D vision for the first time at age 48. This book was fascinating and explained so many things about vision that I had never thought about before. After reading these two books, I understood enough to know that I had to do whatever it took to get Zach to do what Dr. Boyles and Candice, Zach’s vision therapist, instructed us to do for homework each week. When the bifocals arrived, Zach put them on and looked at a book. “Mama! This book has LETTERS in it!!” he yelled excitedly. “What did they used to look like?” I asked, with tears in my eyes as I began to really understand his 3 years of struggle. “They used to look like hairy gray blobs,” he told me. Hairy gray blobs. He could read hairy gray blobs a year and a half above his grade level. I wondered what his reading level would have been if he had been able to see the letters well from the kindergarten? At this point, some people might ask how he ever learned the alphabet in the first place. When he was a baby, I had purchased a set of foam letters about 3 inches tall for use in the bathtub. During bath time, his dad would play with 4 or 5 letters with him until he knew the names of them. Then he would trade them for 4 or 5 different letters. When he was first diagnosed with vision problems at age 2 ½, his visual acuity was tested the first time using the adult Snellen chart after the ophthalmologist had switched his screen to the large letter E and Zach had identified it. It may sound crazy but researchers have now developed a curved LCD screen that can fit over the human eye. There's also more practical uses for these contacts such as adaptable sunglasses. The UV-Rays can trigger the contact lens to go dark in order to protect the eye. Would you wear these contacts? Amazing documentary about a blind boy who used echolocalisation to navigate his way around. When we are in front of the computer or reading for long periods of time, this can cause stress on the eyes. To avoid this, there are a few tips to follow:

1. Have 2-5 minute breaks every half an hour from reading to allow your eyes to rest and recover. 2. When reading, make sure that your reading material is at least Harmon Distance or "Elbow Distance" away. The distance is measured by placing a closed fist under the chin and resting the elbow on a table. The point at the end of the elbow represents the closest distance a person should be from their near work. 3. Try to spend the same amount of time outdoors as you do indoors. This gives your eyes the visual stimulus to relax when outdoors. Remember, when the eyes are looking out into the distance that's when the eyes are most relaxed. When the eyes are looking up close at a book or computer screen, that's when the eyes are working at its hardest. These tips should be followed not only through high school, but throughout your adult life. Sounds easy? Don't forget to do this the next time you're reading! Ever wondered how optical illusions worked? Beau Lotto explains how optical illusions are created and touches on the complexities of the human brain. Sheila Nirenberg talks about the ground-breaking technological advances in developing a prosthetic eye. |

Copyright © 2024 Student Eyecare Pty Ltd ABN: 94 153 954 959